Ancient Egyptian Mummy Reveals DNA of Black Death Pathogen

A groundbreaking discovery has been made by archaeologists examining an Egyptian mummy from the Museo Egizio in Turin, Italy. Researchers have identified remnants of the Black Death pathogen, Yersinia pestis, in the DNA of the ancient mummy, revealing the presence of one of history’s most devastating pandemics far beyond its previously understood range.

This marks the first time the plague has been identified in ancient Egypt, providing new insights into the global reach of this disease that claimed millions of lives throughout history.

The Plague and Its Deadly Legacy

The Black Death, caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, is best known for its catastrophic impact in Europe during the mid-14th century. The pandemic, which began in 1347, is believed to have arrived via trading ships that carried infected rats. Witness accounts describe sailors covered in black boils oozing blood and pus—a hallmark symptom of the bubonic plague.

Samples of the Black plague were found in a mummy in Italy. Credit: Stefano Guidi/Getty

Within just four years, the plague decimated approximately one-third of Europe’s population, killing an estimated 25–30 million people. Its devastation was not confined to Europe, however, as Asia and the Middle East also suffered heavy losses.

Discovery in Egypt: The Mummy’s Secret

The mummy in question is an anthropogenically mummified adult male, radiocarbon-dated to the period spanning the end of Egypt’s Second Intermediate Period and the beginning of the New Kingdom. While the exact location of the mummy’s origin within Egypt remains unknown, the discovery of Y. pestis DNA in its remains suggests that the plague reached Egypt far earlier than previously documented.

The research team employed a shotgun metagenomics approach to analyze bone tissue and intestinal content from the mummy. This method allowed for the detection of Y. pestis DNA, which revealed the advanced progression of the disease in the individual.

“This is the first reported prehistoric Y. pestis genome outside Eurasia, providing molecular evidence for the presence of plague in ancient Egypt,” the team announced at the European Meeting of the Paleopathology Association.

Although the findings do not confirm how widespread the plague was in ancient Egypt, the discovery broadens the historical understanding of the disease’s geographic and temporal spread.

How the Black Death Spread

The plague spread through flea bites from fleas infected with Y. pestis, which often traveled on black rats. Poor sanitation, crowded living conditions, and expansive trade routes allowed the disease to move rapidly, devastating populations in its path.

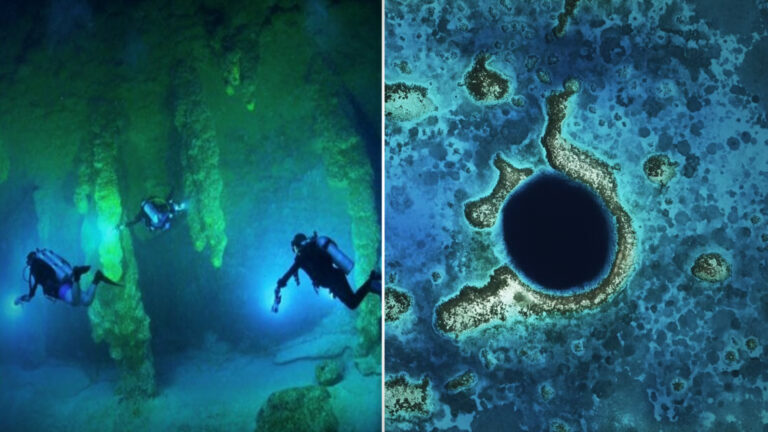

Painting shows a scene of people suffering from the bubonic plague in the 15th century from the Toggenberg Bible. Credit: Bettmann / Contributor/Getty

The disease presented in three primary forms:

- Bubonic Plague (most common): Characterized by swollen lymph nodes, or “buboes.”

- Septicemic Plague: Infects the bloodstream, leading to tissue death.

- Pneumonic Plague: Affects the lungs and is the most deadly and contagious form.

Victims often succumbed to the disease within days, making the discovery of Y. pestis DNA in a well-preserved mummy remarkable.

The Plague’s Enduring Presence

While the Black Death is often regarded as a historical event, Y. pestis has not been eradicated. Small outbreaks continue to occur globally, often linked to wild animals like prairie dogs and squirrels.

In 2024 alone, cases were reported in Oregon and New Mexico, with one man succumbing to the disease. Evolutionary geneticist Paul Norman explained:

“There still are little pockets of plague in the U.S. It circulates in wild animals, but it is treatable with antibiotics.”

Modern medicine has greatly reduced the lethality of the disease, though these sporadic cases serve as a reminder of its resilience.

Implications of the Discovery

This discovery is significant for several reasons:

- Geographical Expansion: It demonstrates that the plague was present in North Africa long before its European outbreak, suggesting the disease had a far broader range than previously believed.

- Historical Context: By uncovering Y. pestis DNA in a mummy, researchers can explore how ancient civilizations might have experienced and responded to outbreaks of disease.

- Public Health Insights: Understanding the ancient spread of infectious diseases like the plague offers valuable insights for modern epidemiology, particularly in tracking zoonotic pathogens.

As researchers continue to analyze the mummy’s DNA and contextualize the findings within ancient Egyptian history, the discovery could reshape how we understand pandemics in the ancient world.

The Persistence of Disease Through Time

The reemergence of the Black Death in modern times and its newfound presence in ancient Egypt highlight the persistent nature of infectious diseases throughout human history. While advancements in medicine and public health have mitigated its impact, the Y. pestis bacterium remains a potent reminder of humanity’s ongoing battle with infectious pathogens.

This mummy, preserved for millennia, serves as a silent witness to a disease that shaped human history—and whose shadow still lingers today.

Featured Image Credit: Marc Deville/Getty